It wasn’t easy being the weird outsider creative kid growing up in the Fundamentalist church. I constantly berated myself for being an “over-analyzer” as though this was a fault rather than an asset. I struggled to conform to the unified whole, but was always left with the same person hiding inside my head. Secretly, I knew that the only path to my complete self was through diversity—of thought, of lifestyle, of culture. I knew this, though everyone around me kept saying over and over, “Be in the world, but not of it.”

I began drawing obsessively from about the age of seven, and by my teens was doing figurative paintings in oils. People were often impressed by my work, yet the feedback I most remember is, “These are beautiful, but when are you going to start bringing glory to God?” I took this to mean that if I wasn’t painting scenes from the Bible, my art had little value. This was the basic concept of what an artist should be. The entire back wall of the church was covered in tacky oil paintings depicting the life of Jesus.

I was trained to mistrust everything outside of our tightly woven sub-culture. I not only looked down on people who were not Christian, but I feared them as well. I absorbed these lessons of conformity, and though none of it felt right, I was afraid to ask questions. A question meant doubt, and doubt could result in my family, my friends, my church, my school, rejecting me. It was a narrative I had observed before, and one I was to experience to some extent later on.

These memories came up strongly for me as I did research from two books written by Christian writers—Art For God’s Sake by Philip Graham Ryken, and State Of The Arts by Gene Edward Veith, Jr. The two authors seek to “educate” the reader with a call to reclaim art for their faith, as though art should not be determined by the artist, but by the establishment. Ryken begins by observing the issues within the church for artists, with words that ring true to what I experienced:

“If anything, things are even more difficult for Christian artists. Some churches do not consider art a serious way to serve God. Others deny that Christians in the arts have a legitimate calling. As a result, Christian artists often feel like they have to justify their existence. Rather than providing a community of support, some churches surround them with a climate of suspicion (Ryken, 9).”

The individual artist is not only underestimated in their role, but also feared in their ability to examine and critique the system. The church is leery of this type of behavior since their ideology is based on faith rather than fact. From his fair assessment, Ryken’s treatise quickly devolves into a derailment against the art world, and the two writers—Ryken being strongly influenced by the work of Veith—go on to display their lack of education on modern art, and their inability to explore the work beyond face-value:

“In many ways the art world has become—in the words of critic Suzi Gablik—a ‘suburb of hell (Ryken, 13).’”

Along with sweeping generalizations of the non-believing artist:

“It has always seemed to me a great evidence for the Christian faith that those who reject it acknowledge, if they are honest, that without God they have no hope in the world (Ephesians 2:12). Great unbelieving artists generally do not pretend that the absence of God in their lives is in any way fulfilling or a cause of rejoicing. Lacking God, they express their own emptiness. Looking outward, they probe and find that everything—other people, their society, nature itself—is a sham and a cheat. Is not their experience exactly what the Christian would predict (Veith, 210)?”

Veith’s observation here is a classic projection of his own beliefs onto those with an entirely different set of values. He holds assumptions about their worldview and their experience, concluding that they must be depressed and confused. I can’t comment for other artists, but since I am an unbelieving artist with greatness left to be determined, I take offense to Veith’s view. The only sham is the idea of God itself. With a bit of historical research, it doesn’t take much to understand that all gods pass away. The people who have created them, however, continue on in their formation of ideas.

Personally, when I first realized that God does not exist, I suddenly understood the concept of self-responsibility. There is no outside source directing my course. It is all on me—my choices, my initiative, my discipline. There is no one to blame for a misstep but myself. This redirection brought a sense of presence. I became more of a problem-solver. Fully embodied in nature, I no longer found it suspect. Rather than looking beyond this existence, I found the enormity of the present. There was nothing empty about this experience, and it improved my work as an artist.

“But whatever stories it tells, and whatever ideas or emotions it communicates, art is true only if it points in some way to the one true story of salvation—the story of God’s creation, human sin, and the triumph of grace through Christ (Ryken, 40).”

If a believing artist chooses to fall in line by directly promoting the church—as the church so often requests—their art degrades into propaganda. The general viewer is not interested in an art show as a form of religious proselytization. Rather, the audience seeks metaphor and examinations of established ideas. When a power structure uses the artist as a vessel for the promotion of a prerogative, the artist is subtracted down to the role of artisan. Yes, under a patron the artist may toy with the limits of their role, or use their artistry to go above and beyond, but the subject matter is typically chosen for them. Before the Renaissance, artists were generally viewed as artisans, and they received little respect in society.

Through many centuries of power, the Catholic Church understood the sway that art could have on their congregation. They staked their claim on visual artists, funding them and commissioning major works of art. Since most people could not read, the art served as the narrative. Though this set-up has changed drastically since then, the view that the church should direct the course of the art, still persists.

During the Reformation, as early Protestants sought to differentiate themselves from Catholicism, they destroyed many works depicting saints, and their fervor led to a general mistrust of art as being idolatrous. As a result, artists in Northern Europe faced a shortage of patrons for their work, and suddenly they had to paint of their own accord, without a commission directing their course. Subject matter shifted from religious and mythical depictions to scenes from everyday life.

Inadvertently, this rejection of visual art by the Protestant church led to the artist as a free agent. As the ideas of Humanism developed, art evolved as an ever-shifting landscape, wide and varied. It went beyond the limits of “beauty” and became a process of experimentation and exchange. When the individual is given value, there are no borders on creativity. We now benefit from the conceptual artist not only in art itself, but also in science, technology, and so many other aspects of contemporary life.

The problem between Christianity and art lies in the essence of both. Christians are told to not ask questions by accepting the mythical as being true. The artist is instructed to examine the details of every concept, and dissect the visual down to its basic elements to build it back up again.

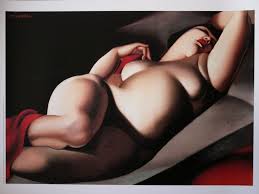

It makes sense that everything I wanted to express as a young girl was in opposition to the limits imposed on me. In response to being instructed that a woman must be submissive, I painted strong women that I wanted to emulate. In order to work through my fear that the “darkness” would consume me, I dove right into it, and found that if you face it without fear, it has no power and does not even exist. I wanted to understand what made the world evil, and all I found was a world full of stories that only make sense when you listen, when you search, when you read from start to finish.

The thing is, even when you make these realizations, you still have to live in a world inhabited by people who think that myths are true. I have let go of my anger enough to have a dialogue with the people who tried to make me something that I was not. And since I am not a Christian, I can ask as many questions of believers as I choose. I keep them on their toes, and we have all grown for it. Every day, I lose another piece of the fear that I was raised with. It turns out, that being an “over-analyzer” was my greatest strength, not my greatest weakness.